Imagine you are a public health policy maker in a large country. You learn that if the entire adult population of your country would take a drug would increase survival by about 12%, and that in 4.1 years almost 1.5 million people would be prevented from dying.

Would you recommend the drug?

Now, imagine you are an individual living in that country. You learn that the government wants you to take a drug. Compared to not taking the drug, about 150 people will need to take it to prevent one additional death in 4.1 years. There may be side-effects.

Would you take the drug?

Both situations involve the same drug!

But how can this be? Saving almost 1.5 million people, but at the same time so many people need to take the drug before one person is saved.

We’re going to see how in this and the following post about risk difference, relative risk reduction, and number needed to treat.

We’ll also learn about how if we are only shown the relative risk reduction, the impact of the drug may be overblown.

This will also demonstrate some important issues between the public health and the individual.

Risk Difference

This is actually a pretty simple calculation. We have already seen calculations related to this in the relative risk and odds ratio posts. Some of the concepts will carry over.

The risk difference is also known as the absolute risk reduction.

Just like in the risk ratio and odds ratio, we have 2 groups, one gets the treatment and the other the placebo (or no treatment). We are measuring an event occurring or not occurring. To calculate the risk difference we just:

- count up the number of events in the treatment group

- divide by the total number of subjects in that group

- count up the number of events in the placebo group

- divide by the total number of subjects in that group

- Subtract the results of step 2 from step 4.

Basically, we are calculating an incidence rate for each group, and taking the absolute value of the difference. It is the risk of event for the treatment group minus the risk of event in the control or placebo group.

The formula for the risk difference is:

CI = cumulative incidence, and the t and c subscripts indicate the treatment and control groups.

Why cumulative incidence?

The risk difference is a time sensitive measurement. Different incidence rates would be obtained with different study lengths, even using the same treatment. So cumulative means up until the point when the study ends.

A real world example:

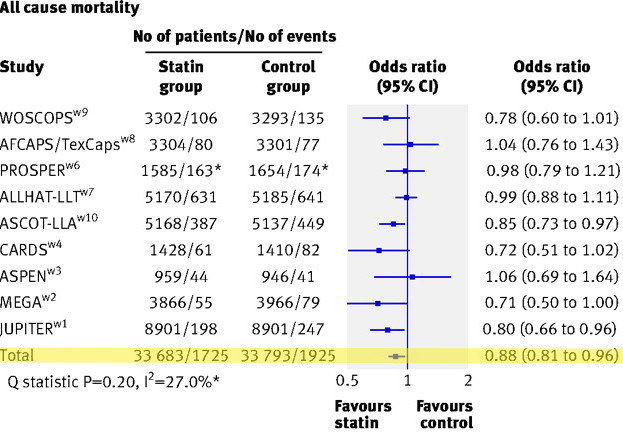

The following chart is from a meta-analysis regarding Statins. Statins are a group of drugs that lower cholesterol, which in theory should reduce cardiovascular disease. This has been borne out in studies, but the whole subject is not without controversy. This meta-analysis (study of studies) we will look at uses the endpoint or event of interest all cause mortality (not just from cardiovascular disease). That just means death from anything. If you die, you are included as an event occurrence. The population that the study analyzed was people with cardiovascular risk factors, but not cardiovascular disease.

This should look pretty familiar if you’ve read some of the previous posts on odds ratios and risk ratios. The chart shows the columns: Study (which study the data is from), Statin group (the treatment group), Control group (placebo), Odds ratio chart with 95% Confidence Interval, and Odds ratio with 95% CI.

The Statin group and Control group show the total numbers of subjects / the number of events (death).

Look only at the Total row, highlighted above. That’s all the studies combined. Note that the odds ratio’s 95% confidence interval does not include 1, it is (0.81 to 0.96). Remember that that means the treatment is ‘significantly different’ from the control group.

Risk Difference Calculation

We can easily calculate the risk difference using the steps outlined above. The number of events and total subjects for each group are given to us.

Control group: 1925 / 33683 = 0.05696446

Statin group: 1725 / 33793 = 0.05121278

Those are the cumulative incidence rates for control and treatment groups. The numbers do look pretty close.

Note that these are pretty low incidence rates.

Now we can calculate the risk difference.

Looks very small doesn’t it?

This risk difference of 0.00578 was not reported in the study, although it can be calculated easily. Instead another measure, the relative risk reduction was reported.

Relative Risk Reduction

This tells us the how much the treatment group differs from the control group taking into account the initial incidence rate of the control group. Because the risk difference is time sensitive, this is also a time sensitive measure. Usually it is shown as a percentage.

Or, the risk difference divided my the incidence rate for the control group.

That’s 10.1% So according to the meta-analysis, statins reduced all cause mortality by 10.1% in 4.1 years.

Ah, yes, that’s what I wrote in the first part of this blog post. The drug would increase survival by about 12%.

Ok, I overestimated slightly. Actually, it wasn’t me! The study authors reported a “12% risk reduction in all cause mortality compared with the control.”

12%?

If you round up the intermediate calculations, divide by the treatment group (not control group) then round up the result, you will get 12%. Usually, in fact every formula I’ve seen for the relative risk difference, uses the control group as the denominator because you are comparing it to the treatment to that group. I am not sure why the authors of the study did not do that. Even using their rounded results: |5.1-5.7| / 5.7 = 10.52%

Risk Difference vs. Relative Risk Reduction:

I’d like to draw your attention to a common practice used when results like these in the meta-analysis above are calculated. When you see headlines or advertisements, you will usually see the relative risk reduction. This is because it looks more impactful. Remember the values in this study:

Risk difference: 0.00578

Relative risk reduction: 10.1% (or 12% as the authors say)

This is what would appear in the headline: Statin therapy reduces risk of death by 12%!

But remember, that reduction is relative to how many people would die in the first place.

You won’t see the headline: Statin therapy reduces risk of all-cause mortality by 0.00578!

Risk of dying without Statins: 0.057

Risk of dying with Statins: 0.051

This is not incorrect. It is an equivalent mathematical way to state the results. It is not equivalent in an informational way. You must be aware of how it works. Basically, to determine the real impact, you need more information than just the relative risk reduction.

An Simple, Extreme Example

Imagine that there is a very rare disease. It kills 2 people in 1,000,000. A new drug is developed. It saves the life of 1 person if everyone takes the drug everyday for 10 years.

Let’s calculate the risk difference and the relative risk reduction:

Relative risk reduction: |2/1000000 – 1/1000000| / (2/1000000) = 0.5 or 50%

50% relative risk reduction! You can see the articles now. “New drug reduces risk of death by 50%!”

Hold on. Let’s calculate the risk difference.

|2/1000000-1/1000000| = 0.000001

What does that mean? Your probability of dying from the disease was 0.000002. If you take the trug, your probability of dying from the disease is now 0.000001.

I think you can see the problem with just reporting the relative risk reduction.

Back to the Top

Remember in the beginning of the post I said that the drug could save almost 1.5 million people in 4.1 years?

That drug is the same drug from the meta-analysis: statins.

How could it save so many people?

Let’s imagine that the adult population of our country is 250 million. That might be the approximate adult population of a certain large country…

With the incidence rate(probability of event occurrence) and the total adult population we can calculate the number of deaths for each group.

Placebo or control group (no drug): adult population million * incidence rate for control group = number of deaths

250,000,000 * 0.05696446 = 14,241,115 deaths

Remember, that’s in 4.1 years.

Treatment or Statin group: adult population * incidence rate for treatment group = number of deaths

250,000,000 * 0.05121278 = 12,803,194 deaths

Difference: 14,241,115 – 12,803,194 = 1,437,921 lives saved (in 4.1 years)

Almost 1.5 million.

That is something that public health policy makers will have to talk about.

Number Needed to Treat

I said that this drug requires about 150 people to take it before 1 person is saved.

How does that work?

Stay tuned for the next episode!

Summary

Risk Difference is an absolute measure, calculated by the formula:

It shows the difference in risk of the treatment and control groups.

Relative Risk Reduction is a relative measure, calculated by the formula:

It shows the reduction in risk relative to the control incidence rate.

These are both important public health measures.

To make an informed decision, you need the context of the relative risk reduction. What is it relative to? The risk difference can help here. So can the Number Needed to Treat, which we will see in the next post.

P.S. There are even more complications to figuring out the actual number of people that a drug will save or help and if it’s worth it to take the drug. In our statin example, all of the results are based on a meta-analysis. A study of studies. But not all studies are included in this analysis. The authors excluded some, perhaps for valid reasons, perhaps not. You have to decide. How to determine what will be included and not included? What is the quality of the studies in the first place? What are the costs of taking the drug? Side effects? What population did the study analyze? Are your characteristics similar to the study’s population? etc…

It’s complicated.

One thought on “Risk Difference & Relative Risk Reduction”